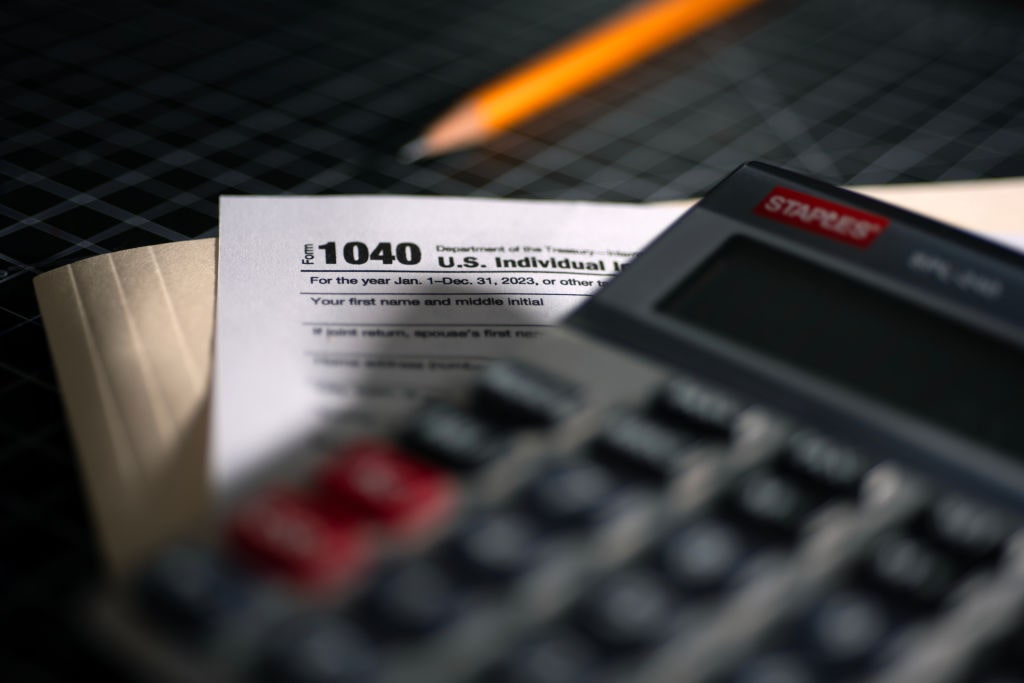

Is a value-added tax (VAT) the solution to America’s fiscal woes? This is the murmur on CNBC. While politicians would rub their hands and lick their lips at this revenue tool, it would enable officials to maintain the status quo and continue running persistent budget deficits. What makes anyone think more taxes and revenues are necessary to restore fiscal discipline in Washington?

Value-Added Tax Talk

CNBC recently published an opinion piece by Peter Tanous, author and the founder and chairman of Lynx Investment Advisory, titled “A value-added tax is one solution to the crippling debt problem.” He was realistic in his assessment of the fiscal dilemma in the nation’s capital: mandatory spending accounts for much of the annual budget, defense and interest expenses represent most of the discretionary outlays, and neither Republicans nor Democrats are willing to touch entitlements.

What’s the solution? He proposed a VAT on the business news network’s website: “There is only one way to raise the amounts that will make a difference and reduce the deficit: Do what every other developed country has done and institute a value-added tax.”

What’s the solution? He proposed a VAT on the business news network’s website: “There is only one way to raise the amounts that will make a difference and reduce the deficit: Do what every other developed country has done and institute a value-added tax.”

A VAT is a consumption tax comparable to a sales levy. However, a VAT would be applied to each stage of a good’s production and distribution rather than at the final point of sale. Additionally, it would be an indirect penalty because consumers would not pay the tax at checkout.

Over the years, experts have assessed the subject. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a non-partisan budget watchdog, estimated in December 2022 that a 5% VAT would raise between $1.9 trillion and $3.05 trillion over a decade. The Brookings Institution, a right-of-center think tank, noted more than a decade ago that the United States would join 150 countries that have implemented a VAT and highlighted “that the VAT can raise substantial revenue, is administrable, and minimally harmful to economic growth.”

While the chief argument is that it will impact low-income Americans since it is inflationary and regressive, Tanous noted that a tax credit would be an easy solution. However, he conceded that Congress will wait for a major crisis before action is taken.

Is giving Washington more money a plausible solution? Not really. Federal receipts are already close to an all-time high of $5 trillion, and spending is at a record of approximately $7 trillion (President Joe Biden’s latest budget is nearly $8 trillion). Would $3 trillion over ten years help plug shortfalls, shore up Social Security, and tackle the national debt? If history is an indicator of how the elephants and donkeys behave in Uncle Sam’s kingdom, funds are wasted on war, interest, and political agendas when the government receives more money.

The Rise of ‘Problem’ Banks

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) recently published a first-quarter report without much fanfare. One of America’s top financial regulators confirmed the worst: “unusually high unrealized losses” surged $39 billion to $517 billion, and the number of “problem” banks on the brink of a collapse increased to 63. Although the banking system was resilient in the January-March span, the FDIC conceded that the financial sector is still grappling with a wide range of “significant downside risks” from high inflation, elevated interest rates, and geopolitical turmoil.

“These issues could cause credit quality, earnings, and liquidity challenges for the industry,” the FDIC said. “In addition, deterioration in certain loan portfolios, particularly office properties and credit card loans, continues to warrant monitoring.”

Canada Cuts Interest Rates

Canada, the home of Double Doubles and Tim Bits and the land of World Economic Forum experiments, became the first G7 nation to cut interest rates. The Bank of Canada pulled the trigger on a quarter-point cut, lowering its key interest rate from 5% to 4.7%. This was the first reduction since March 2020 and was widely expected because inflation is inching toward the central bank’s 2% target, and the economy has weakened considerably.

How much will this weigh on the Federal Reserve? It might not impact the Eccles Building, but it does show that monetary authorities are willing to ignore their arbitrary 2% inflation target rate. Since Ottawa was still several months from reaching the promised land, market watchers might believe the US central bank could be willing to cut rates early enough, particularly as the US economy shows signs of slowing down.