Did Andy Warhol steal Prince’s image from rock ‘n’ roll photographer Lynn Goldsmith? That’s the question the Supreme Court heard Wednesday, Oct. 12, and the answer could change the fortunes of many, as well as the art of the nation. Goldsmith shot the artist formerly, then once again, known as Prince for Newsweek in 1981. A few years later, Andy Warhol used the photo for a creation of his own. Should Warhol’s estate have paid Goldsmith, or was it a fair use allowed by America’s copyright laws? This case is extremely high profile without being ideological.

Baby I’m a Star

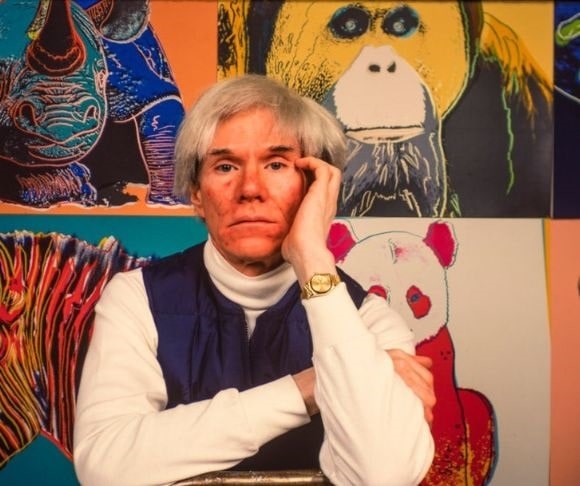

Vanity Fair licensed Ms. Goldsmith’s photos of Prince in 1984. The magazine sent the image to Warhol, commissioning the pop art movement icon to produce something with it. He made 14 silkscreen prints and two pencil illustrations based on the Goldsmith photograph. Here are Goldsmith’s photo and Warhol’s prints:

After Prince’s death in 2016, Vanity Fair ran another of Warhol’s Prince images and paid a $10,250 licensing fee to the Andy Warhol Foundation to publish it. Goldsmith was making some rumblings that she might go after them for copyright infringement, so the foundation went to court first. It asked a federal court to decide that Warhol’s Princes did not violate copyright. Goldsmith countersued and lost round one when the judge ruled the fair use doctrine protected Warhol’s works. She appealed, and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with her, ruling against Warhol.

When Doves Cry

Photographers own the reproduction rights to the images they capture. No one can use the image without permission from the owner unless they meet an exception to that rule. The only reason Liberty Nation may reproduce the images shown above without a license, for instance, is because of a copyright exception for news reporting purposes. The foundation says Warhol’s work is permitted because he sufficiently transformed the original image into something new, which makes it his own. The Second Circuit ruling said the silkscreens were “much closer to presenting the same work in a different form,” more similar to a “derivative” work like an art reproduction than a transformative one.

During oral arguments at the court, the justices seemed likely to disagree with the appellate court. Justice Elena Kagan said:

“[M]useums show Andy Warhol … because he was a transformative artist because he took a bunch of photographs, and he made them mean something completely different; and people look at Elvis, and people look at Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor and Prince, and they say this has an entirely different message from the thing that started it all off and that’s why he’s hanging up on those museums …”

Justices Sotomayor and Chief Justice Roberts’ discussion seemed to put them in with Kagan’s transformative view. Arguments from the bench were not all one-sided, however. Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested that Warhol’s Prince image may not be entitled to fair use protection because its essential purpose is similar to that of Goldsmith’s original photo: to display a portrait of the singer in a magazine. He contrasted this with a more clear-cut example of transformation: Referencing Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s Tomato Soup poster, Gorsuch said the artist’s purpose “was not to sell tomato soup” but to “induce a reaction from a viewer.”

Justices Sotomayor and Chief Justice Roberts’ discussion seemed to put them in with Kagan’s transformative view. Arguments from the bench were not all one-sided, however. Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested that Warhol’s Prince image may not be entitled to fair use protection because its essential purpose is similar to that of Goldsmith’s original photo: to display a portrait of the singer in a magazine. He contrasted this with a more clear-cut example of transformation: Referencing Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s Tomato Soup poster, Gorsuch said the artist’s purpose “was not to sell tomato soup” but to “induce a reaction from a viewer.”

Nothing Compares 2 U

There has been a torrent of interest in this case, with many amicus briefs filed by interested parties. Dr. Seuss’ estate, the music industry, and the photographers’ associations want tight standards restricting copyrighted material in fair use. They will lose some control over their works and, perhaps more importantly, revenue opportunities if the Court rules in favor of the Warhol Foundation. Documentarians, free marketeers, and artists who depend on the fair use exception want a broader reading. Their creativity and financial success depend on wide latitude to create new works. Warhol died in 1987. He said, “The idea is not to live forever; it is to create something that will.”