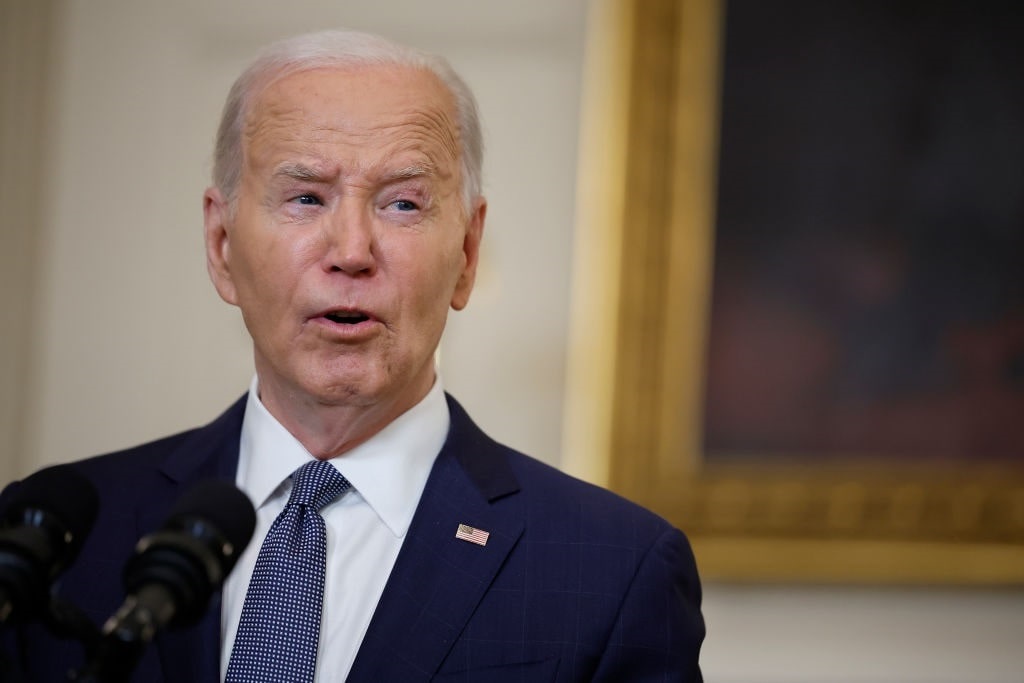

With polls following the conviction of Donald Trump not moving in the direction Democrats had hoped, at least in the week following their cherished verdict, indications are that the panicked party is devoting much of its attention to maintaining control of the Senate. This apparent though subtle shift away from an overwhelming emphasis on the presidential race is based on hard data showing down-ballot Democrats running well ahead of Joe Biden and holding their own in must-win Senate races.

The most yawning gap between up- and down-ballot in battleground states is in Arizona, where Trump leads Biden by an average of four points, according to Real Clear Politics (RCP), but in the race for Senate, Democrat Ruben Gallego is comfortably ahead of Republican Kari Lake by almost seven points. In Pennsylvania, Trump leads by more than two points, but Democratic Sen. Bob Casey is 5% ahead of Republican challenger David McCormick. In Wisconsin, the presidential race is tied, but incumbent Democratic Sen. Tammy Baldwin is nine points up on GOP challenger Eric Hovde. And in Nevada, Trump leads by more than 5%, but Democratic incumbent Jacky Rosen leads both candidates vying for the GOP nomination by about two points.

The most yawning gap between up- and down-ballot in battleground states is in Arizona, where Trump leads Biden by an average of four points, according to Real Clear Politics (RCP), but in the race for Senate, Democrat Ruben Gallego is comfortably ahead of Republican Kari Lake by almost seven points. In Pennsylvania, Trump leads by more than two points, but Democratic Sen. Bob Casey is 5% ahead of Republican challenger David McCormick. In Wisconsin, the presidential race is tied, but incumbent Democratic Sen. Tammy Baldwin is nine points up on GOP challenger Eric Hovde. And in Nevada, Trump leads by more than 5%, but Democratic incumbent Jacky Rosen leads both candidates vying for the GOP nomination by about two points.

That means, on average in these four crucial swing states, Democratic candidates for the Senate are running nine points ahead of their incumbent president. And Democrats are well aware of what’s at stake. If their archenemy returns to the White House, control of Congress will at least allow the left to damage him with greater force and thwart his every legislative initiative as they did the first time around. Five months out from Election Day in a race that has been surprisingly stable over several months – Trump leading by 1-2 points nationally and ahead or even in the swing states – the question is whether similar stability will also take hold in races for the Senate, which are just now coming into focus.

Democrats have long known they had a challenging path to maintaining their 51-49 majority in the upper chamber in 2024, defending 23 of the 33 seats in play (there are also three special elections unlikely to affect the balance of power). Most of those seats are safe, but three clearly are not, and a new monkey wrench was just thrown into their plans that could well put a fourth state in play and complicate Democrat efforts to maintain their narrow control of the Senate. Disgraced New Jersey Sen. Bob Menendez, who escaped prosecution once but is now on trial again for bribery, has left the Democratic Party but decided to enter the race for his seat as an independent. Democrat Andy Kim had built a comfortable lead over Republican Curtis Bashaw, but with Menendez likely to draw votes due to his name recognition and experience, the left-of-center vote could well be split, sending Bashaw to Capitol Hill. That is exactly what happened in the New York Senate race in 1970, when long-shot James Buckley, brother of the famous William F. Buckley running on the Conservative Party line, was elected with less than 39% of the vote when the liberal Republican and Democrat split the left-of-center vote.

Biden Should Be So Lucky

In Ohio, left-wing Sen. Sherrod Brown is ahead in a race where polling is all over the place. Five of the latest polls in the Buckeye State, where Biden is trailing by ten points, show Brown leading by an average of nine, though four other surveys show his GOP challenger, Bernie Moreno, up by an average of 4%. In Montana, where Biden is behind by 20 points, the incumbent Democrat, centrist Jon Tester, is ahead by an average of 6% in the four polls conducted in 2024. For those of you not mathematically inclined, that is an almost incredible 26-point gap.

However, it is a radically different story in bright-red West Virginia, where Trump scored his greatest margin of victory in 2020. Moderate Democrat Joe Manchin was able to reliably hold down a Senate seat there since 2010 before he left the party and decided not to seek re-election. With his departure, Republican and sitting Governor Jim Justice has predictably opened up a massive 30-point lead over Democrat Alex Mooney.

However, it is a radically different story in bright-red West Virginia, where Trump scored his greatest margin of victory in 2020. Moderate Democrat Joe Manchin was able to reliably hold down a Senate seat there since 2010 before he left the party and decided not to seek re-election. With his departure, Republican and sitting Governor Jim Justice has predictably opened up a massive 30-point lead over Democrat Alex Mooney.

So, the Dems will likely need to win all four of the aforementioned battleground Senate races – in Arizona, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Nevada – and hold on for dear life in Ohio and Montana just to achieve a 50-50 tie in the upper chamber. So far, as elsewhere across the land, their prospects down-ballot look substantially better than those of Joe Biden.

Ticket-Splitting in a Divided Nation

Ticket-splitting peaked during Richard Nixon’s landslide victory over George McGovern 52 years ago, when nearly 30% of voters cast ballots for different parties for Congress and President, according to Alan Abramowitz, professor emeritus at Emory University who has studied historical trends in divided voting. But such ticket-splitting has reduced significantly over the last half-century, reaching an all-time low of 7% in 2020, according to Abramowitz. “It’s certainly possible we could see some higher rates of ticket-splitting, but I would be surprised if it were as high as what we are seeing in recent polling,” he told Politico. “The phenomenon of negative partisanship is just so high right now.”

There have been many instances of congressional candidates doing their best to distract attention from the top of the ticket. In 1972, Democrats did all they could to separate themselves from McGovern, the most left-wing presidential nominee in history at the time. They did the same with doomed incumbent Jimmy Carter in 1980 and with Walter Mondale as he was getting crushed by President Ronald Reagan in 1984. Their success was limited, with Democrats maintaining substantial House majorities in each instance, but ceding control of the Senate by losing a remarkable 12 seats in 1980.

But the most famous example of successful distancing from top to bottom of the ticket went the opposite way. With public approval of his presidency wavering as he faced re-election in 1996, and chastened by a shocking Republican takeover of the House two years earlier, President Bill Clinton made a decision that would come to define his bid for a second term. He declared in his State of the Union address that “the era of big government is over,” even though we now realize it never was, and adopted an ideological stance that would come to be known as triangulation. Signing off on welfare reform and a hard-edged crime bill, he positioned himself squarely in the center lane while congressional Democrats went left and Republicans right. With the strong tailwind of a healthy post-Reagan economy at his back, Clinton sailed to victory over the late Bob Dole.

The intriguing question this year is the extent to which the voters will triangulate, splitting their tickets between Republicans and Democrats. After all, we have been hearing for months about the broad unpopularity of both Biden and Trump, even though Trump easily dispensed with some impressive opposition throughout the GOP primary. What’s to stop voters from holding their noses and voting for a president they don’t much like, and then balancing it off by voting for the other party down-ballot? Democrats are quietly, even surreptitiously, attempting to present this as a viable option for voters displeased with the top of the ticket. The question is whether they can sell the electorate the narrative that, despite the transparent cognitive and political decline of the presidential nominee, their party remains vital at the state and local levels. They better hope the voters buy it.